AI prompts are essential to helping researchers get the most out of the AI tools they are using – whether that’s ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity or a specific AI tool for qualitative research, like Beings. On first glance it may seem as though prompting is simple – especially with the conversational way AI chatbots are designed to help you feel as though you are speaking with a person. However, great prompting is the key to unlocking AI’s potential in your research workflow.

Good prompts turn AI from simple “grab and return” knowledge, to a research co-partner. In some cases, depending on the capability of the tool, even creating a partner that’s akin to the skillset of a Senior Research Analyst to work alongside you.

Whatever the model or tool, prompts need to be clear and have solid boundaries, with a firm sense of what matters. Most researchers adjust their prompts through repeated attempts during early analysis, which helps them find a structure that holds the output close to the transcript. This learning curve is normal, but below is a “cheatsheet” to help you go from basic prompts, to master prompter.

Why clear prompting matters in qualitative research

Clear AI prompting shapes how well the analysis stays connected to the material provided. If the requests via prompt are loose or vague, then the summaries sometimes edge towards neat statements that flatten detail or introduce meaning that wasn’t expressed in the session.

This can send researchers down the wrong path, and cause them to lose nuance or interesting interpretation of the material.

How prompting evolves during qualitative analysis

In practice, the main constraint in qualitative analysis is rarely the AI. It is often the researcher’s own learning curve, particularly around what they ask for and when. In a recent customer session we conducted, a researcher described struggling to get more value from probing and follow-up, not because the AI tool fell short, but simply because they were unsure of how to direct it.

Early in analysis, prompts tend to be more broad because researchers are cautious about introducing bias or over-steering the material. This is usually an appropriate start, helping to establish what is present in the data and provide a stable overview before the direction is applied.

As familiarity with the material grows, prompting should naturally become more focused. Researchers begin to narrow attention, asking AI to take a look at specific themes, identify and compare differing perspectives, or even to leave out areas (anti-patterns) that are either already understood or are not relevant to the research aims.

10 useful AI prompts for qualitative research

The 10 qualitative research prompts below are designed to work well in Beings, the AI tool for qualitative research, or another AI tool of your choice. They show how to frame a clear, bounded request and can be used as written, or adjusted to suit your study.

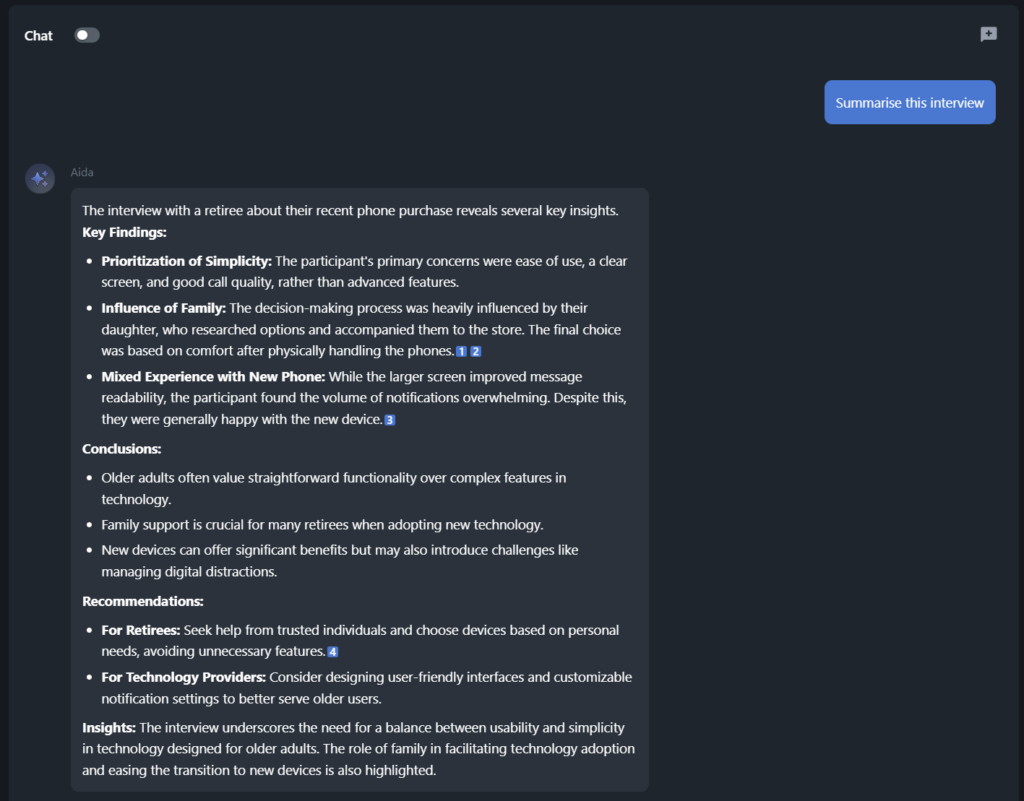

1. Start with a broad overview prompt

A simple summary prompt is a useful starting point because it provides direction without steering the analysis too early. It gives a clear sense of what the participants discussed, but without directing the structure or prioritisation.

Prompt:

“Summarise this interview”

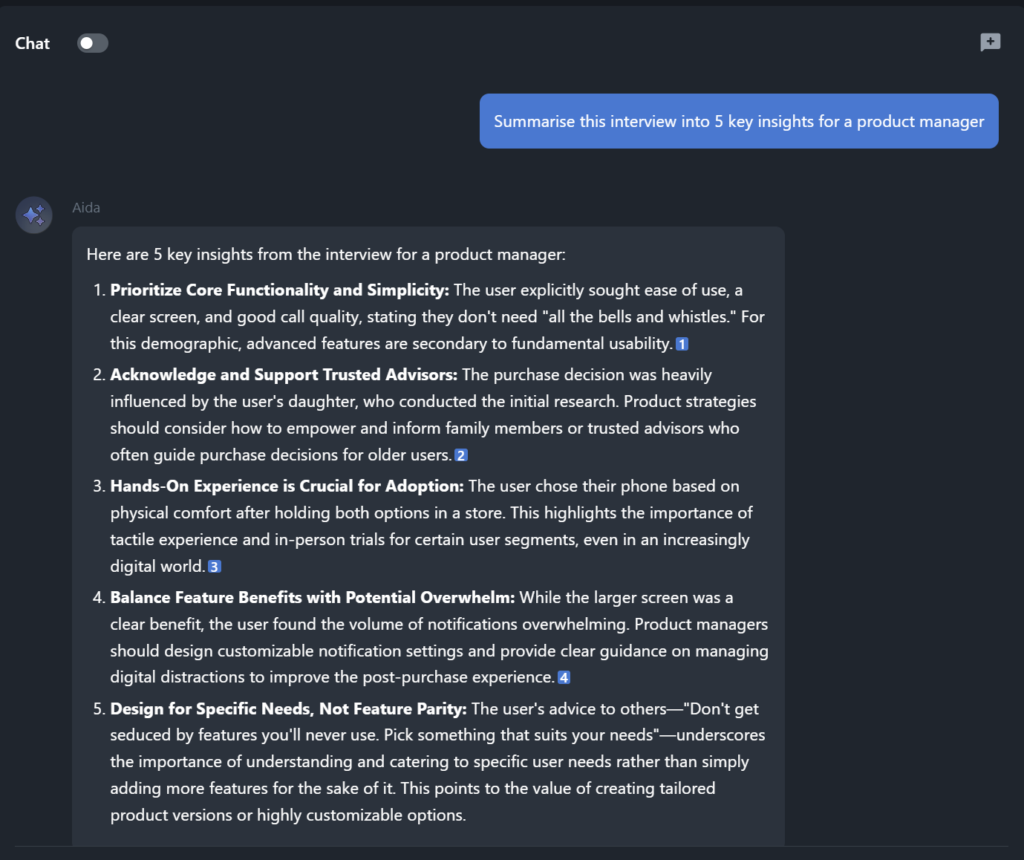

2. Add light structure without steering

When needed, add context to make the output more usable without narrowing the scope too far. Specifying audience or format introduces light structure while keeping the focus on what was said.

Prompt:

“Summarise this interview into 5 key insights for a product manager.”

3. Create a full thematic frame

Once an initial overview is established, a more structured prompt can be used to organise the material into themes that are ready for synthesis and sharing. This type of prompt spells out the form that the output should take, which helps turn transcriptions into a coherent reporting framework, without skipping straight to conclusions.

Prompt:

“Analyse all interview transcripts and produce a thematic analysis with the following elements:

– key themes with short descriptions

– supporting participant quotes for each theme

– summaries of participant perspectives

– a comparison across participants

– implications drawn directly from the findings.”

4. Identify what mattered most

Once themes are visible, this prompt will help to prioritise what carried the most weight for participants. It shifts the analysis from listing issues to understanding which ones mattered most, without introducing any interpretation or recommendations too early.

Prompt:

“From the issues identified, which one was the most important or most frustrating for participants? Explain why.”

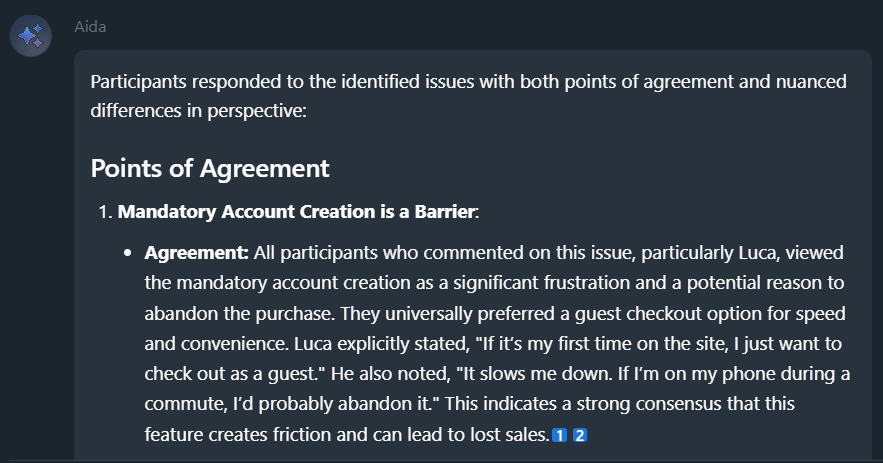

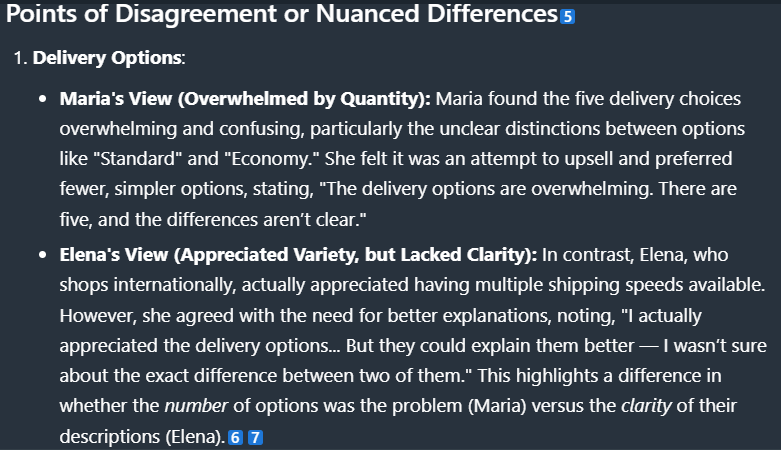

5. Compare perspectives across participants

After identifying what mattered most to participants, this prompt helps prevent the analysis from collapsing into a single story. It highlights how participants differ in what they focus on and how they describe their experiences, keeping individual perspectives visible rather than averaging them out.

Prompt:

“How did participants respond differently to these issues? Show points of agreement and disagreement.”

6. Zoom in on emotional weight

Once key issues are clear, this prompt helps to distinguish between topics that were mentioned and those that carried intensity. Emotional cues often signal how strongly participants felt about an issue, which can help to adjust how findings are treated later, but without assigning meaning too early.

Prompt:

“What emotions did participants express when discussing these issues?”

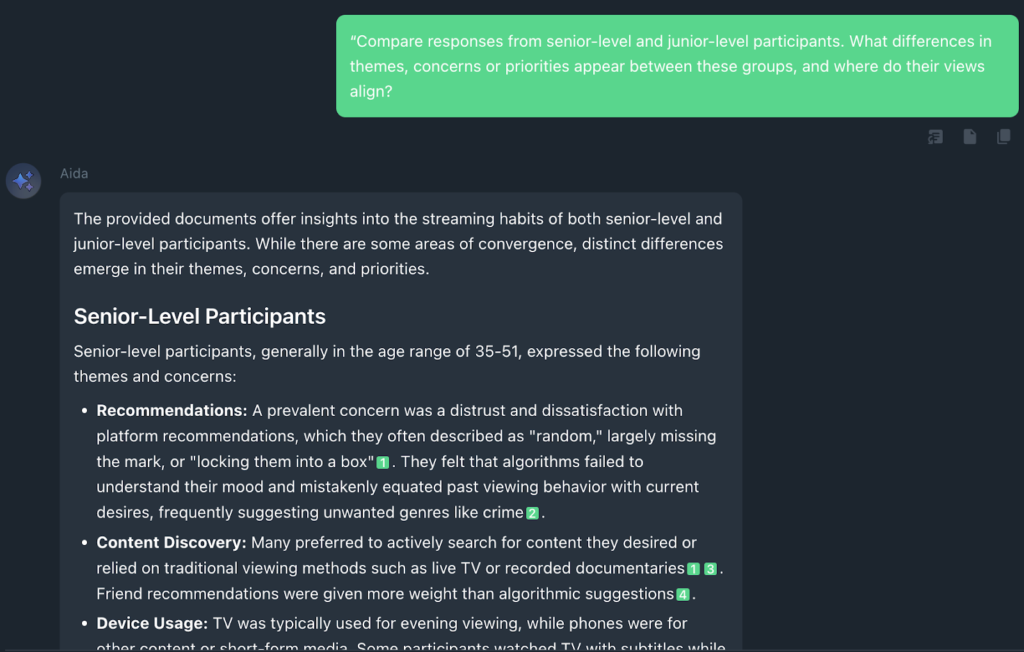

7. Highlight any assumptions the participants expressed

At this stage, prompts can be used to help surface the expectations the participants bring to the situation. Comparing responses across, for example, seniority levels, often reveals differences in priorities or mental models that are easy to miss when looking at responses in aggregate. This kind of segmentation is useful in organisational research, where barriers often sit between roles rather than within them.

The same approach can be applied in consumer research, where differences in segments, such as first-time users or experienced customers, can shape how needs and frustrations manifest.

Prompt:

“Compare responses from senior-level and junior-level participants. What differences in themes, concerns or priorities appear between these groups, and where do their views align?”

Alternatively, a more general prompt:

“Identify underlying assumptions in the participants’ responses. Where do different participant segments hold conflicting beliefs?”

Or:

“Identify the underlying assumptions or ‘mental models’ that seem to be driving participant behavior. Move beyond what they did, and explain why they likely did it based on the evidence.”

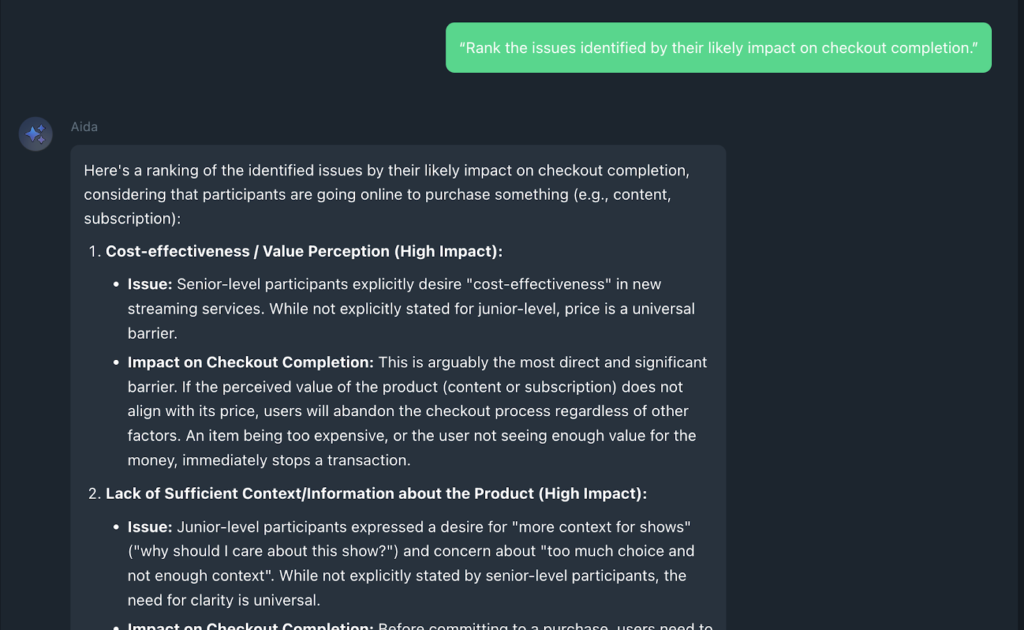

8. Prioritise by likely impact

Once differences and assumptions are visible, this prompt helps to move from description to consequence. It supports prioritisation by asking which issues are most likely to affect outcomes, rather than which ones were easiest to recall or most frequently mentioned. This then helps teams to focus attention without turning to analysis too early.

Prompt:

“Rank the issues identified by their likely impact on checkout completion.”

9. Move from description to meaning

At this point, the groundwork is now in place. This prompt supports interpretation by asking what the findings suggest, rather than restating what was said. Because it builds on earlier structure and prioritisation, meaning can now be explored, without losing contact with the source material.

Prompt:

“Based on these issues, what do they suggest about the participants’ expectations of an e-commerce checkout?”

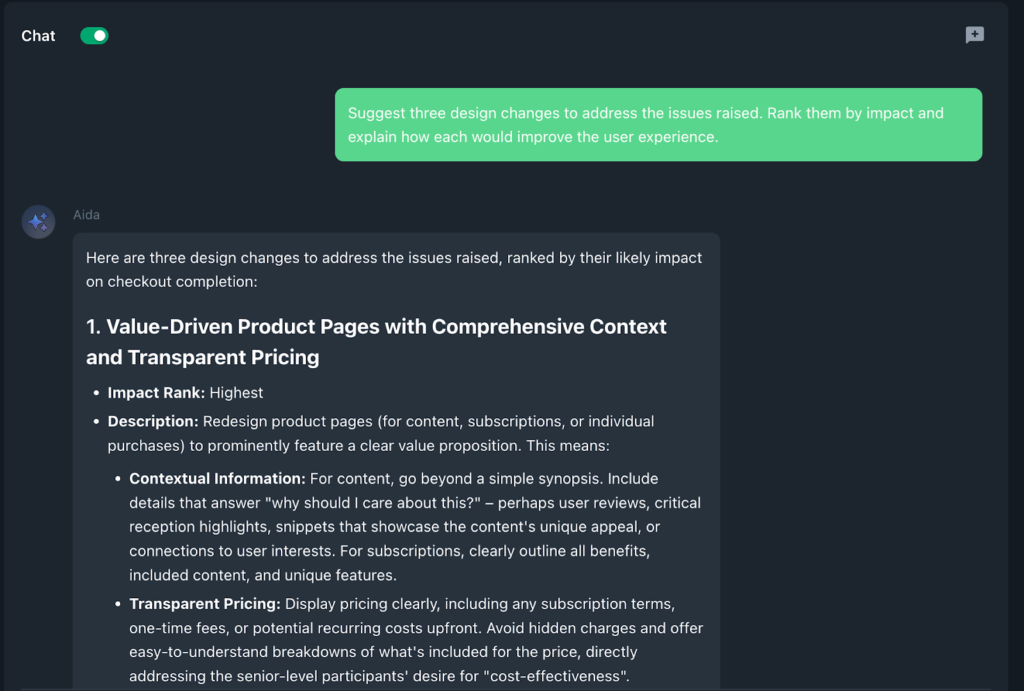

10. Translate insight into action

This prompt can be used once analysis and interpretation is completed. It shifts the work from insight to decision by asking how findings could inform change, while keeping a clear link back to what participants actually raised. Used at this stage, recommendations are grounded in evidence rather than instinct.

Prompt:

“Suggest three design changes to address the issues raised. Rank them by impact and explain how each would improve the user experience.”

How to write more effective prompts for research

The prompts above are a great starting point for research, following a methodical strategy. However, in practice, qualitative researchers often move back and forth between the different stages, revisiting earlier questions or challenging ideas, as new patterns surface. What matters is not the exact wording of each prompt, but how it is used to manage scope and keep the analysis connected to the material. This is further supported by Beings, because each quote or viewpoint provided by Aida is linked back to a timestamped section of the audio or file.

When it comes to creating your own prompt library, it’s good to remember that effective prompts tend to follow four main caveats:

1) They control scope

Starting with open summaries and moving towards a more focused comparison later on in the process.

2) They signal what kind of thinking comes next

Rather than specifying a rigid format, prompts point the analysis in a particular direction for the next line of enquiry, such as identifying concerns raised by participants or looking at how perspectives differ by seniority.

3) They place limits on interpretation

Effective prompts make clear what should be avoided at any given stage, such as drawing conclusions or moving into recommendations too early. These limits keep the analysis close to the source material, particularly during the early and mid-stage of exploration.

4) They build on what has already surfaced

Prompts work best when they respond directly to earlier outputs rather than from scratch each time. A comparison prompt can follow an overview, prioritisation follows theme identification and interpretation and recommendations can only come when the differences and assumptions are understood. This allows the analysis to develop cumulatively.

A simple way to check whether a prompt will surface what you need is to run it against this checklist..

Does it match the stage of analysis?

Is it broad enough for early orientation, or does it deliberately refer back to themes, differences, or priorities that have already surfaced?

Does it signal what you want next?

Are you asking for an overview, a comparison, a prioritisation, or a step towards interpretation?

Does it state what to avoid?

If needed at this stage, does it make it clear what to avoid, such as an anti-pattern?

Does it build on what you already know?

Is the prompt responding to earlier outputs rather than starting from scratch each time?

Running through this check will help to keep prompts purposeful and should reduce the risk of drift as the analysis unfolds.

Beings helps you refine prompts across transcripts and sessions

With Beings, a lot of the interpretation that would come with a more generic AI model is already stripped out. The Beings tool is designed and built specifically for qualitative research documentation and analysis, so it automatically stays close to the wording of the participant and retains the shape of the session in view as you move through it. This means that prompt work is lighter as you are not constantly correcting drift, hallucinations, or stripping out added meaning.

As you work through your material, you can reuse the same prompt patterns across transcripts by simply selecting multiple recordings and files within a project workspace. This allows you to keep a consistent approach even when the study becomes more complex.

Over time, this builds a natural rhythm, and you begin to see what a strong prompt looks like in practice because the output reflects it clearly.

Start Using Structured AI Prompts Inside Beings

To try it for yourself, you can begin shaping and refining your own AI prompts for research inside Beings. Create a free account by signing up and start working with your own material straight away.